Note: This site is moving to KnowledgeJump.com. Please reset your bookmark.

Transfer of Learning

Transfer of Training — That almost magical link between classroom performance and something which is supposed to happen in the real world - J. M. Swinney.

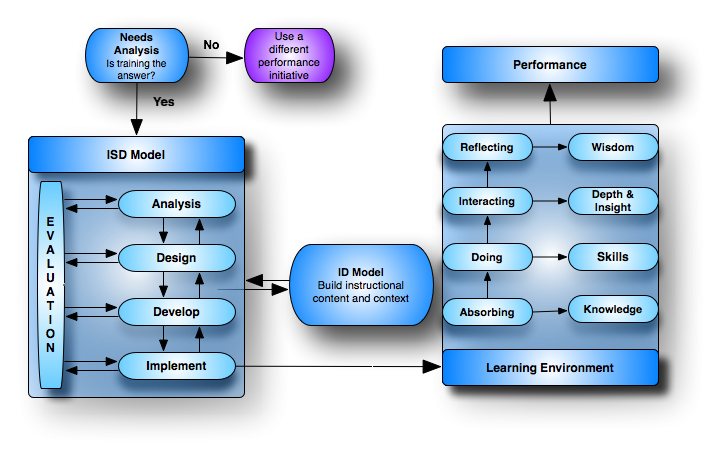

Transfer of training is effectively and continuing applying the knowledge, skills, and/or attitudes that were learned in a learning environment to the job environment. Closely related to this concept is Transfer of Learning—the application of skills, knowledge, and/or attitudes that were learned in one situation to another learning situation (Perkins, 1992). This increases the speed of learning.

In a backhoe course where I once taught, we had about twenty machines consisting of three different models. One model was an old Massy-Ferguson. Its controls consisted of about eight levers that only moved back and forth. The newest model was a John Deere. It had two joystick-type controls (they moved similar to a computer joystick) and two foot-pedals. The other model was a Case that was a cross between the other two.

The learners took turns operating the various models. Although a casual observer unfamiliar with transfer of learning might assume we were confusing the issue with three highly different models, the different models were not only conductive to the learning environment in that they provided transfer of learning (hence quicker and deeper learning), but they also provided the learners with the confidence and skills for transferring their newly acquired skills to the job.

The first place to practice transfer of learning is within the classroom. This makes it much easier to transfer new skills and knowledge to the job. Transfer of learning is the influence of prior learning on performance in a new situation. If we did not transfer some of our skills and knowledge from prior learning, then each new learning situation would start from scratch.

Some learning professionals only think of transfer of learning (or transfer of training) in terms of the classroom to the job environment. However, these trainers fail to realize the importance of task variation within the classroom. That is, practicing on a variety of tasks will enhance and quicken the learning process as compared to practicing in the same category or class. This helps the learners to become accustomed to using their newly acquired knowledge and skills in novel situations, thus encouraging transfer of learning to the job.

Transfer of learning is a phenomenon of learning more quickly and developing a deeper understanding of the task if we bring some knowledge or skills from previous learning to a new learning situation. Therefore, to produce positive transfer of learning, we need to practice under a variety of conditions and environments.

Note that there is a brief slow down in the learning curve (confusion occurs) when the variation is first introduced. However, the variation soon begins to strengthen our previously acquired skills and knowledge. This is perhaps why some trainers are reluctant to use task variation—they see the initial confusion and assume they are slowing and confusing the learning process. Hence, classrooms and other learning environments become sterile of transfer of learning. And since the learners have no practice in transferring their newly acquired skills and knowledge in the classroom, they have trouble transferring their learning when they return to the job as most work environments are neutral towards the transfer of new skills (that is, they do very little to encourage the transfer of learning). Do NOT fall into this trap. Variation is GOOD! Provide as many variations and conditions in the learning environment as possible. There are two main principles that work with transfer of learning:

- The variation should not be too easy.

- The shift or transfer should be progressive but rapid.

For example, introductory computer classes often follow a course similar to this:

- — One module of introduction

- — One module of word processing

- — One module of spreadsheet

- — One module of database training

Why not combine the four modules into integrated classes that goes similar to this:

- Starting the three applications

- Typing text into the three applications

- Copying and pasting in the same application and then to a different application

- Saving, editing, etc.

The above are closely related tasks that would enhance the power of transfer of learning.

We benefit (or suffer) from our prior experiences. People improve in their ability to learn new skills more proficiently because of prior practice on a series of related tasks. This helps us to acquire new views on a topic by looking at the task from a different approach, which strengthens our understanding of the topic. For example, practicing to drive a variety of cars provides experience with different stimulus situations and makes new learning easier. Another example is that greater learning occurs not by rereading the same text, but by reading another text on the same subject matter.

This can be carried further with the use of examples. Do not just provided one or two examples, but rather a variety of them. Once you have provided a few examples that support the concept, and the learners are starting to get a firm grasp of the new concept, then you may introduce some examples that contradict the concept. This is similar to using non-examples for enhancing learning (see Positive Reinforcement Activity for Leaders for an example).

Transfer of learning begins with the learning of a task in a unique situation and ends when we quit learning (experimenting) with that task. The power of varied context, examples, different practice scenarios, etc. cannot be overemphasized. No matter if you are learning simple discriminations or complex concepts, stimulus variations are helpful. Encouraging transfer of learning in the classroom provides the skills and knowledge for its successful implementation outside of the class.

Theory of Formal Discipline

It was once thought that taking courses such as Latin would lead a person to think more logically. This assumption is called the "Theory of Formal Discipline." Thorndike (1923) studied it and concluded that the expectation of any large difference in general improvement of the mind from one study to another was false.

The main reason why it looks as if good thinkers have been helped by taking certain school studies is that the there is an inherent tendency of the good thinkers to take such courses. When the good thinkers studied Greek and Latin, these studies seemed to make good thinking.

Thorndike continued his study of transfer, and eventually formulated the Theory of Identical Elements—previous learning facilitates new learning only to the extent that the new learning task contains elements identical to those in the previous task.

Near and Far transfer

Transfer of learning can be divided into two categories, Near and Far (Cree, Macaulay, 2000).

Near transfer of skills and knowledge are applied the same way every time the skills and knowledge are used. Near transfer training usually involves tasks that are procedural in nature, that is, tasks which are always applied in the same order. Although this type of training is easier to train and the transfer of learning is usually a success, the learner is unlikely to be able to adapt their skills and knowledge to changes.

Far transfer tasks involve skills and knowledge being applied in situations that change. Far transfer tasks require instruction where learners are trained to adapt guidelines to changing situations or environments. Although this type of training is more difficult to instruct (transfer of learning is less likely), it does allow the learner to adapt to new situations.

References

Cree, V. E., Macaulay, C. (2000). Transfer of learning in professional and vocational education. Routledge, London: Psychology Press.

Perkins, D. N., Salomon, G. (1992). Transfer of Learning. Contribution to the International Encyclopedia of Education, Second Edition. Oxford, England: Pergamon Press.

Thorndike, E. L. (1923). The influence of first year Latin upon the ability to read English. School Sociology. 17: 165-168.