Note: This site is moving to KnowledgeJump.com. Please reset your bookmark.

Performance Coaching

Achieving excellence through performance is accomplished in two major ways. The first way is taking a proactive stance by unearthing or preventing counter-productive methods. For example, you might implement diversity and sexual harassment training programs before they become a problem within the organization.

The second way is to correct performance problems as they arise within the organization. This is accomplished by first, identifying the root cause and secondly, implementing a plan of action to correct the problem. Although people are our most important asset, it sometimes seems as if they are our biggest headache. Both training and coaching are are used to help fix performance problems when part of the solution requires learning, but each uses a different approach: 1) training uses a structured design to provide the employees with the knowledge and skills to perform a task, while 2) coaching is a process that helps the employees gain greater competence and overcome barriers to improve job performance on a as needed basis..

Coaching has been defined as 1) the processes of encouraging the individual to improve both job skills and knowledge (Hahne & Schultze, 1996), 2) to assist in problem solving or mastering new skills (Bittel & Newstrom, 1996), 3) and the process of providing others with valuable information so that the organization learns (Schon, 1983).

There are four major causes of performance problems:

- Knowledge or Skills - The employee does not know how to perform the process correctly - lack of skills, knowledge, or abilities.

- Process - The problem is not employee related, but is caused by working conditions, improper procedures, etc.

- Resources - Lack of resources or technology.

- Motivation or Culture - The employee knows how to perform, but does so incorrectly.

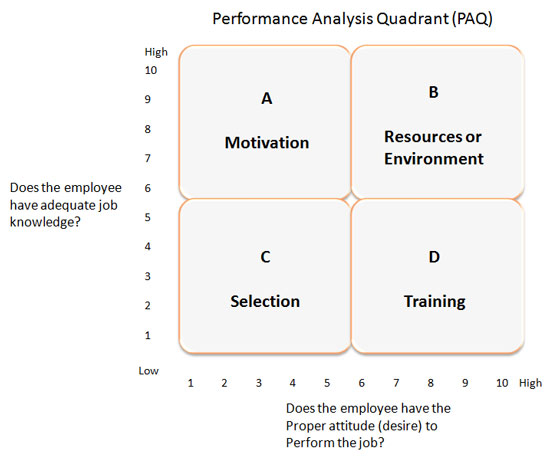

PAQ

The Performance Analysis Quadrant (PAQ) is a tool to help in the identification. By asking two questions, “Does the employee have adequate job knowledge?” and “does the employee have the proper attitude (desire) to perform the job?” and assigning a numerical rating between 1 and 10 for each answer, will place the employee in 1 of 4 the performance quadrants:

- Quadrant A (Motivation): If the employee has sufficient job knowledge but has an improper attitude, this may be classed as motivational problem. The consequences (rewards) of the person's behavior will have to be adjusted. This is not always bad as the employee just might not realize the consequence of his or her actions.

- Quadrant B (Resource/Process/Environment): If the employee has both job knowledge and a favorable attitude, but performance is unsatisfactory, then the problem may be out of control of the employee. i.e. lack of resources or time, task needs process improvement, the work station is not ergonomically designed, etc.

- Quadrant C (Selection): If the employee lacks both job knowledge and a favorable attitude, that person may be improperly placed in the position. This may imply a problem with employee selection or promotion, and suggest that a transfer or discharge be considered.

- Quadrant D (Training and or Coaching): If the employee desires to perform, but lacks the requisite job knowledge or skills, then additional training or coaching may be the answer.

The solution does not have to be the same as the cause. For example, you can often fix a process problem with training or perhaps fix a motivation problem with attitude or (affective domain) coaching.

While coaching may be used for all four problems depending on the circumstances, it is best used for Quadrant D—Training and/or Coaching. Large groups are generally dealt with training as it is more efficient, while coaching is used for small groups; however, coaching is normally required during training due to individual needs.

Note: The four quadrants are based on Jones' (1993) description of the four factors that affects job performance.

A - Motivation

Often the employee knows how to perform the desired behavior correctly, the process is good, and all resources are available, but for one reason or another, chooses not to do so. It now becomes a motivational issue. Motivation is the combination of a person's desire and energy directed at achieving a goal. It is the cause of action. Motivation can be intrinsic - satisfaction, feelings of achievement; or extrinsic - rewards, punishment, or goal obtainment. Not all people are motivated by the same thing, and over time their motivation may change.

Although most jobs have problems that are inherent to the position, it is the problems that are inherent to the person that cause us to loose focus from our main task of getting results. These motivational problems could arrive from family pressures, personality conflicts, a lack of understanding how the behavior affects other people or process.

When something breaks the psychological contract between the employee and the organization, the leader must find out what the exact problem is by looking beyond the symptoms, find a solution, focus on the problem, and implement a plan of action. One of the worst situations that a leader can get into is to get all the facts wrong.

Start by collecting and documenting what the employee is not doing or should be doing - tasks, special projects, reports, etc. Try to observe the employee performing the task. Also, do not make it a witch hunt, observe and record what the employee is not doing to standards. Check past performance appraisals, previous managers, or other leaders the employee might have worked with. Try to find out if it a pattern or something new.

Once you know the problem, then work with the employee by using coaching techniques to solve it. Most employees want to do a good job, thus they will normally be happy to accept coaching to improve themselves. It is in your best interest to work with the employee as long as the business needs are met and it is within the bonds of the organization to do so.

B - Process or Environmental Problems (Not Related to Employees)

Many performance problems are due to bad process, that is, the process does not support the desired behavior. It has often been said that people account for 20% of all problems while bad processes account for the rest. See the Continuous Process Improvement Page for tracking down inefficient processes.

However, coaching can be used to get people to think about ways to solve the process or environmental problem.

C - Selection

D - Lacks the Skills, Knowledge, or Abilities to Perform

This problem generally arises when then is a new hire, new or revised process, change in standards, new equipment, new policies, promotion or transfer, or a new product. In this case, there is only one solution - training. The training may be formal classes, on-the-job, self-study, coaching, etc. To determine if training/coaching is needed, we only need to ask one question, “Does the employee know how to perform the task?” If the answer is yes, then training is not needed. If the answer is no, then training is required. However, this page will focus on coaching skills.

Coaching Skills

Some people tend to use the terms coaching, mentoring, and training interchangeably. However, there are differences. Mentoring is often thought of as the transfer of wisdom from a wise and trusted teacher. He or she helps to guide a person’s career, normally in the upper reaches of the organization. However, this perception is starting to change as organizations are now implementing mentoring at all levels of the company's structure.

NOTE: Mentor comes from the age of Homer, in whose Odyssey; Mentor is the trusted friend of Odysseus left in charge of the household during Odysseus's absence. Athena, disguised as Mentor, guides Odysseus's son Telemachus in his search for his father. Fénelon in his romance Télémaque (1699) emphasized Mentor as a character, and so it was that in French (1749) and English (1750) mentor, going back through Latin to a Greek name, became a common noun meaning wise counselor. Mentor is an appropriate name for such a person because it probably meant adviser in Greek. |

Training is about teaching or instructing a particular skill or knowledge and is normally given in a formal environment.

Coaching, on the other hand, is about increasing an individual's knowledge and thought processes with a particular task or process. It creates a supportive environment that develops critical thinking skills, ideas, and behaviors about a subject. Although it is closely tied to training, it is more personal and intimate in nature.

The main difference between a coaching and a training is that the former is normally done in real time. That is, it is performed on the job. The coach uses real tasks and problems to help the learner increase his or her performance. While with training, learning is performed within the classroom.

Mentoring is more career developing in nature, while training and coaching are more task or process orientated. Also, mentoring relies on the mentor's specific knowledge and wisdom, while coaching and training relies on facilitation and developmental skills. Although there are these differences, you could say that the three are synergistic and complementary, rather than mutually exclusive as most people would agree that a good coach trains and mentors, a good trainer coaches and mentors, and a good mentor trains and coaches. A performance coach is also a:

- Leader - who sets the example and becomes a role model.

- Facilitator - is able to instruct a wide verity of material.

- Team Builder - pulls people into a unified team.

- Peace Keeper - acts as a mediator.

- Pot Stirrer - brings controversy out in the open.

- Devil's Advocate - raises issues for better understanding.

- Cheerleader - praises people for doing great.

- Counselor - provides intimate feedback.

In order to coach, it helps to use a few facilitating techniques:

- Draws people out:

- “What do others think?” or “What do you think?”

- “I've heard from (name) so far. . . are there any other thoughts?”

- “And what else?”

- Silence (20-30 seconds) - gives the person a chance to think. Also, people tend to abhor silence, thus if you wait long enough, the person will usually speak up.

- “You look like you have something to say. . .”

- Interprets comments:

- Words verses tune or tone (many questions are not really questions but a need for self-assurance).

- Intent verses wording (learners often have a hard time wording new subject matters).

- Sees beyond the learners paradigms and filters.

- Clarifies thoughts or comments:

- Use models and experiences to bring life to the subject.

- Looks for multiple points to expound on the subject.

- Looking for similarities and differences.

- Senses group energy:

- Sparks up the group with various energizers.

- Takes breaks as needed.

- Has a sense of timing.

- Handling objections:

- Try not to personalize (the learner will become defensive).

- Reflect on the objection for a moment to ensure you understand the objection.

- Encourages conversation.

- Remembers to breath and relax.

- How we treat each other:

- Accepting each other into the group.

- Individual responsibility.

- Being right verses being successful.

- Influence verses dominance (pull rank).

- Confidentiality and trust.

- Supporting each other.

- Active listening.

- Conflict resolution.

To go into further detail, see Coaching Skills and Activity.

Resources

Just because the problem is caused by a lack of resources or technology, does not mean expenditures are needed. Remember, the solution does not always have to be the same as the cause. In this case you might be able to get your team to brainstorm new processes or procedures that will eliminate the need for new resources.

In addition, coaching can be used to get people to try new methods that require less resources.

Causes of problems

Expectations or requirements have not been adequately communicated

This motivational issue is not the fault of the employee. By providing feedback through coaching and ensuring the feedback is consistent, you provide the means for employees to motivate themselves to the desired behavior. For example, inconsistent feedback would be for management to say it wants good safety practices, and then frowns on workers who slow down by complying with regulations. Or expressing that careful workmanship is needed, but reinforces only volume of production.

Feedback must be provided on a continuous basis. If you only provide it during an employee's performance rating period, then you are NOT doing your job.

Also, ensure that there is not a difference in priorities. Employees with several tasks and projects on their plates must be clearly communicated as to what comes first when pressed for time. With the ever increasing notion to do more with less, we must understand that not everything can get done at once. Employees often choose the task that they enjoy the most, rather than the task they dislike the most. And all too often that disliked task is what needs to get performed first.

Lack of motivation

A lack of motivation could be caused by a number of problems, to include personal, family, financial, etc. Use coaching to help employees recognize and understand the negative consequences of their behavior. For counseling techniques see Leadership and Motivation and Confrontation Counseling. For some training exercises see Performance Counseling Activity.

Shift in focus

Today, it's a lucky employee (or unlucky if that employee thrives on change) that does not have her job restructured. Changing forces in the market forces changes in organizations. When this happens, use coaching to ensure that every employee knows:

- How the job changed and what are the new responsibilities.

- Why the job was restructured.

- How their performance be evaluated and by whom.

- New skills they will need to learn.

- What responsibilities will be delegated.

- How their career will benefit from this transition.

- What new skills or training they need to perform successfully.

- How it will make them more marketable in the future.

By keeping them informed, you help to eliminate some of the fear and keep them focused on what must be performed.

Performance Feedback Verses Criticism

In general, there are two different forms of information about performance -- feedback and criticism. Feedback was originally an engineering term that refers to information (outcome) that is fed back into a process to indicate whether that process is operating within designated parameters. For example, the sensor in a car's radiator provides feedback about the engine temperature. If the temperature rises above a set point, then a secondary electrical fan kicks in.

When dealing with human performance, feedback refers to observable behaviors and effects that are objective and specific. This feedback needs to be emotionally neutral information that describes a perceived outcome in relation to an intended target. For example, during a meeting, you announce the tasks and how to perform them. A better way is to ask for input on how the tasks should be performed. This gives people the opportunity to take ownership of their work. People who receive feedback in this manner can use the data to compare the end results with their intentions. Their egos should be aroused, but not bruised.

Compare this to criticism that is emotional and subjective. For example, “You dominate the meetings and people do not like it!” The recipient has much more difficulty identifying a changeable behavior other than to try to be less dominant. Also, the angry tone of the criticism triggers the ego's defensive layer and causes it to be confrontational or to take flight (fight or flee), thus strengthening the resistance to change; which is exactly the opposite of what needs to be done.

Delivering effective performance feedback takes time, effort, and skill; thus people often fall back to criticism. Since we receive far more criticism than feedback, our egos have become accustomed to fighting it off. We have all seen people receive vital information, yet shrug it off through argument or denial, and then continue on the same blundering course.

Receiving Feedback

Being able to give good feedback should not be the only goal; we also must be aware of the need to receive and act upon feedback, even if it is delivered in a critical manner. That is, we need to develop skills that help us extract useful information, even if it is delivered in a critical tone.

Allowing attitudes of the criticizer to determine your response to information only weakens your chances for opportunity. Those who are able to glean information from any source are far more effective. Just because someone does not have the skills to give proper feedback does not mean you cannot use your skills to extract useful information for growth. When receiving information, rather it be feedback or criticism, think “How can I glean critical information from the message?” Concentrate on the underlying useful information, rather that the emotional tones. Also note what made you think it was criticism, rather than feedback? This will help you to provide others with feedback, rather than the same emotional criticism.

The Feedback Process

Giving feedback, instead of criticism, can best be accomplished by following two main avenues:

- Observing behavior - Concentrate on the behavior. Why is it wrong for the organization, team, individuals, etc.; not why you personally dislike it. Your judgment needs to come from a professional opinion, not a personal one. Report exactly what is wrong with the performance and how it is detrimental to good performance.

- Concentrate on pointing out the exact cause of poor performance. If you cannot determine an exact cause, then it is probably a personal judgment that needs to be ignored.

- State how the performance affects the performance of others. Again, if it does not affect others, then it is probably a personal judgment.

- Do unto others, as you want them to do unto you - Before giving the feedback, frame the feedback within your mind.

- It might help to ask yourself, “how do I like to be informed when I'm doing something wrong?”

- What tones and gestures would best transfer your message? Remember, you want the recipient to seriously consider your message, not shrug it off or storm away.

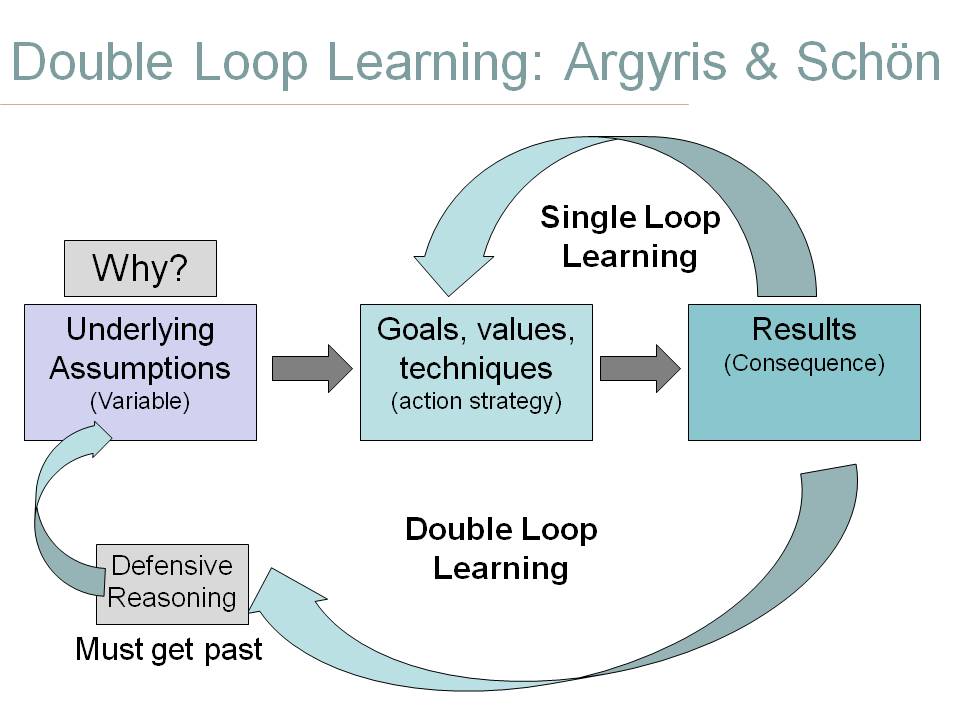

Single-loop and Double-loop learning

Coaching all too often focuses too narrowly on problem solving by identifying and correcting errors. Yet if the coaching is to transfer to the work environment, it must also look inwardly by allowing the learners to reflect critically on their own behavior. Chris Argyris (1991) coined the terms single-loop and double-loop learning.

Single loop learning has often been compared to a thermostat in that it makes a decision to either turn on or off. Double loop learning is like a thermostat that asks “why” — Is this a good time to switch settings? Are there people in here? Are they in bed? Are they dressed for a colder setting? Thus it orientates itself to the present environment in order to make the wisest decision.

A person who is double loop learning is basically orientating herself to all possible solutions within her environment by asking a series of “whys” that is similar to Sakichi Toyoda's (the founder of Toyota) method who used a technique he called the Five Whys — when confronted with a problem you ask “why” five times. By the time the fifth why is answered, you should be at the root cause of the problem.

In Borat's cheesy video shown above, we notice that Borat is learning that all the packages are cheese in one form or another. He might even go on to an advanced cheese class and actually taste some cheeses and learn how to prepare a few dishes. And this is where a lot of coaching ends — at the single-loop learning stage in which we learn about something and how it can solve some of our problems.

Yet Borat still faces the daunting task of actually using his new skills and knowledge in the workplace. And when he meets the slightest form of resistance of putting his new found learnings into action, e.g., “we only use block cheese,” he is going to place the blame on the external environment. This allows any failings to fall upon external forces.

Thus his ability to learn has been shut down at the time that he really needs it the most. Rather than shifting to double-loop learning by asking deep reflective questions on why he cannot do it and then taking action to actually do it, he shifts to a defensive reasoning pattern that ensures any criticisms are shifted to others or to the environment.

For coaching to be the most effective, then we need to allow the learners to look at their own reasoning patterns so that they can detect any inconsistencies between their espoused and actual theories of action.

Note that the supermarket manager is analogous to coaches who only teach “packaging” and pay no mind to the differences in substance. He presented every package as cheese even though the product might have been quite different from variety to variety. For example, Feta and Colby are both cheeses but if a recipe calls for one, they are not normally interchangeable. Distinctions often matter, even if it is only cheese.

Borat seems quite confused that the same product could be offered in so many different packages; he has not yet realized that the product within differs. A good coach allows the learner to go deeper into the process, rather than just gloss over the surface so that when he or she returns to work, they can use their new knowledge and skills in a variety of contexts.

Amusing, but informative video on double and single loop learning (6.21 minutes):

Final Thoughts

Ralph Doherty wrote an interesting article about Commitment vs. Compliance in Beyond Computing (July/August 1998 p. 44):

In compliance environments, employees are told what to do. Although you may turn them loose to perform their jobs, the goals and objectives come from upper-management.

In commitment environments, employees are involved in determining the strategies, directions, and tasks needed to achieve the organization's objective's. This is accomplished by:

- Involve all essential people in developing action plans in areas that are critical to success.

- Identify critical success factors and formulate the plans necessary to achieve those objectives. Everyone in the department, from the front-line workers to managers are used in this process.

- Drive the methodology deeper into the organization by cultivating an environment in which almost everything is linked to employee involvement. The heart of this strategy is by sharing information and involving people at all levels of the organization. Also, hold regular team meetings in which everyone is encouraged to speak what is on their mind.

- Give workers direct access to top management. This keeps top-management in tune with the wants and needs of front-line employees.

By using various coaching techniques to bring them into the process, they understand the problems and have a say in the commitment. This engages their hearts, minds, and hands. . . the greatest motivators of all!

References

Argyris, C. (1991). Teaching smart people how to learn. Harvard Business Reprint 91301. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Bittel, L. Newstrom, J. (1996). Supervisor Development. The ASTD Training and Development Handbook. Craig, R. (ed) New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hahne, C. & Schultze, D., (1996). Sales and Marketing Training. The ASTD Training and Development Handbook, Robert L. Craig (Ed.), 4th ed. (pp. 266-293). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jones, B. (1993). The four domains affecting job performance. Internal Document, Delta Air Lines. Atlanta, GA. As found in, Mancuso, V. (1995). Moving from Theory to Practice: Integrating Human Factors into an Organization. Seattle WA: Annual Flight Safety Foundation Conference. Retrieved Aug 17, 2011 from http://www.crm-devel.org/ftp/mancuso.pdf

Schon, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.