Note: This site is moving to KnowledgeJump.com. Please reset your bookmark.

Left-Brain Right-Brain Metaphor

“In the 1880s, John Hughlings Jackson, a renowned English neurologist, described a patient with right-hemispheres damage who showed selective losses in certain aspects of visual perception—losses that did not appear with similar damage to the left hemisphere” (Levy, 1985).

Levy goes on to describe how others were confirming Hughlings Jackson's findings. At the time, people thought the left-hemisphere was specialized for language, while the right-hemisphere did very little. So while people like Jackson were starting to realize that the right-hemisphere was specialized for many nonlinguistic processes, such as drawing, reading and writing maps, discriminating faces, and other spatial tasks, others were unconvinced of the right-hemisphere's function. Levy goes on to write, “Nonetheless, these were voices in the wilderness, and their views hardly swayed the general neurological community.”

For example, even as late as 1961, neuroscientist J. W. Young thought that the right-hemisphere might merely be a vestige—an organism which have seemingly lost all or most of their original function in a species (Corbalis, Beale, 1976, p.101). So, for quite some time, the right-hemisphere was considered almost wasted space in our cranium. The most it was ever thought to do was to pass information from the left side of the body to the left side of the brain (information from the right side of the body is directed towards the left side of the brain and vice-versa).

It was not until Dr. Roger Sperry came along and erased the prevalent view that people had half a thinking brain. He won a Nobel prize in medicine for his research on patients with split brains. By about 1970, the reign of the left-brain dominance theory was essentially ended.

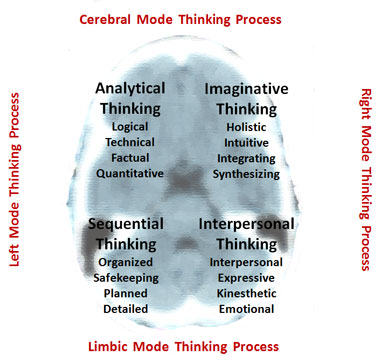

There have been a number of promoters of his theory, perhaps the late Ned Herrmann was one of the most popular. He combined the Triune Brain model of Paul McLean with the Left/Right Brain hemisphere theory of Roger Sperry to form a model of the human brain with two paired structures, the two halves of the cerebral system and the two halves of the limbic system, which means we have four basic thinking styles (Herrmann, 1996, 1999):

Note that we normally prefer one style of thinking which is called the dominant preference. In addition, more than one style may be dominant at a time.

Joseph Hellige (2001), a psychologist at the University of Southern California wrote that researchers have come to see the distinction between the two hemispheres as a subtle one of processing style, with every mental faculty shared across the brain, and each side contributing in a complementary, not exclusive, fashion. A smart brain became one that simultaneously grasped both the foreground and the background of the moment.

As far as each hemisphere being specialized, the only real fallacy is that the left-hemisphere is the "logical" side. Levy writes (1985), “Patients with right-hemisphere damage show more major logical disorders than do patients with left-hemisphere damage.” This only makes sense as our decision-making ability is based upon our emotions.

In short, the reality is that we have two hemispheres that work quite differently. The myth is that they operate independently of each other or only one-side at a time. For example Levy (1985) writes, “there is no activity in which only one hemisphere is involved or to which only one hemisphere makes a contribution.” For example, while we normally think of reading as being a left-brain function, the right side decodes visual information, maintains an integrated story structure, appreciates humor and emotional content, derives meaning from past experiences, and understands metaphors, while the left side is understanding the syntax, translating written words into their phonetic representations, and deriving meaning from complex relations among word concepts and syntax (Levy, 1985).

Perhaps the most important take-away is that when we create learning material, reports, presentations, etc., we should design them to work for both sides of the brain. For example, presentations built solely with bullet points are only aimed at the the left side of the brain. Thus we need to create charts, relevant pictures, etc. so that it is aimed at both sides. Research has shown that you may gain up to an 89% improvement in learning when a relevant visual is added to text (Clark, Mayer, 2007; Clark, Lyons, 2004).

Next Step

Click on the various parts of the chart to learn more about that topic

References

Clark, R. C., Mayer, R. E. (2007). e-Learning and the Science of Instruction. 2nd edition. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Clark, R. C., Lyons, C. (2004). Graphics for Learning. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Corbalis, M., Beale, I. (1976). The Psychology of Left and Right. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hellige, J. (2001). Hemispheric Asymmetry: What's Right and What's Left (Perspectives in Cognitive Neuroscience). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Herrmann, N. (1996). The Whole Brain Business Book, McGraw-Hill: New York.

Herrmann, N. (1999). The Theory Behind the HBDI and Whole Brain Technology. Retrieved May 3, 2010 from: http://www.hbdi.com/home/friendlyDownload.cfm?directory=100024_articles&actualFile=100543.pdf&saveName=Theory-Behind-The-HBDI.pdf

Levy, J. (1985). Right Brain, Left Brain: Fact and Fiction. Psychology Today, May 1985: 19, 38-45.